It has been a challenging year for US South Atlantic ports. AJ Keyes looks at what has been going on and what ports in the region are doing moving into 2024

There is no doubt that 2023 has been a challenging year throughout the North American container port industry. The two major ports in the US South Atlantic region, Savannah, and Charleston, have experienced the same trends as seen elsewhere across the continent, with 2023 volumes down on the comparable period of 2022, with double-digit increases being seen. Despite these challenges, both ports have a clear strategy moving into 2024, as does near-neighbour Jacksonville in northern Florida.

The combination of increasing consumer demand and growing economic activity in the southern states has underpinned recent port demand. The US Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) confirms that in 2010 the northern states generated almost 24 per cent of total US economic GDP, while the southern region provided 21 per cent. By 2022, these figures had shifted to 22.5 per cent and almost 24 per cent, respectively.

This latter shift is shaping the future of South Atlantic ports and their strategic market position. The population of the US Southeast has grown by nine percent since 2012, adding 6.5 million people and increasing consumer demand commensurately. States such as Georgia, South Carolina and Florida are all key markets for both truck and intermodal rail as manufacturing shifts to the Southeast.

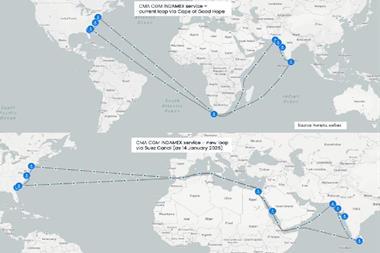

Georgia Ports Authority (GPA) cites the shifting of production sources in Southeast Asia – as customers and ocean carriers respond to a “China plus one” sourcing trend – with India particularly emerging as a strong option. Effectively, this means new business opportunities for US South Atlantic ports because Southeast Asia shipping routes to the US East Coast via the Suez Canal are five days faster than US West Coast routings. This option also overcomes existing Panama Canal water drought challenges which are seeing delays and reduction in the sizes of vessel consignments able to use this All-Water routing – a problem expected to continue in 2024. Admittedly, however, it could also see US South Atlantic ports lose some cargo back to direct transpacific routes to West Coast ports.

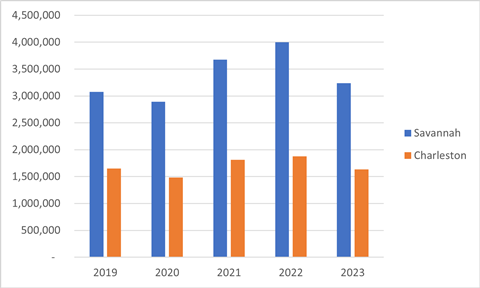

So, while 2023 is proving a tough year for the two major ports in the US South Atlantic region, there is also cause for optimism for 2024 as they build on key longer-term trends. As Figure 1 identifies, for the periods of January through to the end of August for 2019 to 2022, there has been consistent growth for both ports. These periods cover the critical timeframe of the pre-COVID-19 year of 2019, the impact of the pandemic in 2020 and subsequent rebound in 2021 and into 2022.

Consequently, an interesting parallel needs to be drawn with the position before the global pandemic. For example, Savannah’s eight-month 2023 volumes confirm an increase of 4.9 per cent over 2019, while Charleston maintained cargo stability.

BEYOND JUST PORT INFRASTRUCTURE

In October 2023, GPA announced a desire to deepen its access channels from the current 47ft to between 50-52ft and therefore receive ships up to 22,000TEU (from the current largest of 16,000 TEU). A request has been filed with the US Army Corps of Engineers to study the project. Interestingly, these larger ships are carrying volumes of cargo from India that was formerly sourced from China, according to GPA.

The project would likely take about 10 years to complete and comes just 18 months after Savannah completed a US$973 million project to deepen the harbour by five feet to 47ft at low tide.

The other critical infrastructure requirement for Savannah will be the need to raise the Talmadge Bridge, which limits the size of ships able to pass under it, by 20ft from the current 185ft. The Georgia Department of Transportation (GDOT) has developed plans to raise the structure, with completion expected in early 2027, at a cost of up to US$175 million.

It is clear that the ability of ports to handle more cargo and bigger ships involves going beyond the terminal gates, so it is also imperative to continue improvements in port and rail infrastructure too.

Savannah has opened its new 85-acre Mason Mega Rail facility, which doubles port capacity to one million containers per annum and further supports its desire to serve the port’s US Midwest “Arc” target market. In addition, the Garden City Terminal can now serve seven ships simultaneously (including four of 16,000TEU) and is seeing eight new cranes being added between February 2023 and January 2024, while the 100-acre Garden City West expansion has commenced, with one million TEU of annual storage to be added during 2023 and 2024. This will be complemented by two phases of renovations at Ocean Terminal (in 2025 and 2026) to provide two million TEU of annual capacity.

Another development is a new transloading facility adjacent to Garden City Terminal, operated by NFI Industries. It is unique because it does not require a trucker to collect a chassis, then haul the container to a nearby site to transfer the contents into 53ft trucks because the containers are shuttled within the port, thereby also negating access to the South Atlantic Chassis Pool.

BRIDGE ISSUES ALSO IN CHARLESTON

The state of South Carolina has also launched a project to raise the Charleston area’s major bridge as part of a 10-year project aimed at allowing the North Charleston Terminal to receive container ships of up to 20,000TEU in size on Suez Canal routings.

The North Charleston Terminal is the smallest of the Port of Charleston’s three marine terminals and is currently limited to serving ships of up to 8000TEU in size and offers a capacity of just 500,000TEU per annum.

However, raising the Don Holt Bridge from its current 160ft is expected to alleviate these issues, assuming it adds around 25ft in total to air draught. As a result of this project, the South Carolina Ports Authority has confirmed it will increase capacity at the North Charleston Terminal to 2.4 million TEU per annum by re-working the layout and updating equipment.

Upon completion of this terminal investment and the bridge being raised, North Charleston will match capacity at the Wando Welch Terminal. In due course, the Hugh Leatherman Terminal (HLT), currently in its second phase of construction, offers capacity of 700,000TEU per annum, but completion of the phase scheduled for 2032 will also see annual capacity of 2.4 million TEU.

NOT ALL PLAIN SAILING

However, it is not all plain sailing in the US South Atlantic region for Savannah and Charleston. GPA has raised concerns relating to its business model and plans to add a new largescale terminal in the future. In a brief filed with the US Supreme Court, GPA is supporting a September petition from the SCSPA to overturn a court ruling that allows the ILA to sue shipping lines using the Hugh Leatherman Terminal in Charleston as a way to preserve work the union historically performed at other ports.

GPA has already applied to the US Army Corps of Engineers to begin work on Savannah’s third ocean terminal in 2026 and, notably, intends to staff the new 3.5 million TEU facility similarly to all other operating ports — with non-union, state employees operating certain cranes and other lifting equipment essential for the loading and unloading of cargo ships, and union members performing other longshore work.

This is because updating its current hybrid labour model to an all-union workforce will cost “upwards of US$600 million in its first operating year,” GPA states.

The ongoing legal issues in the South Atlantic do come at a cost. HLT in Charleston opened in Q1 2021 but is still largely out of service after the unions sued liner customers in what appears to be a way of dissuading use of the new facility.

Perhaps it is not all bad news though? A Federal Maritime Commission (FMC) administrative law judge has denied an ILA claim dating back to April 2022 that stevedores at the ports of Savannah and Charleston engaged in price fixing. The ruling states that the stevedores are not marine terminal operators with full power to set fees and rates for container handling. A small victory, perhaps, but as shown by the lack of use of HLT, building new terminals and adding capacity to meet demand is only half the challenge – seeing them fully utilised and working harmoniously with union workers must also be achieved.